About me

Motivated and innovative educator with over 8 years of experience teaching English in Kocaeli. I proved my leadership ability and organizational skills by serving as the head of the English department at a private school for 4 years. I took an active role in the central English language groups and contributed to issues such as curriculum development and preparation of educational materials.

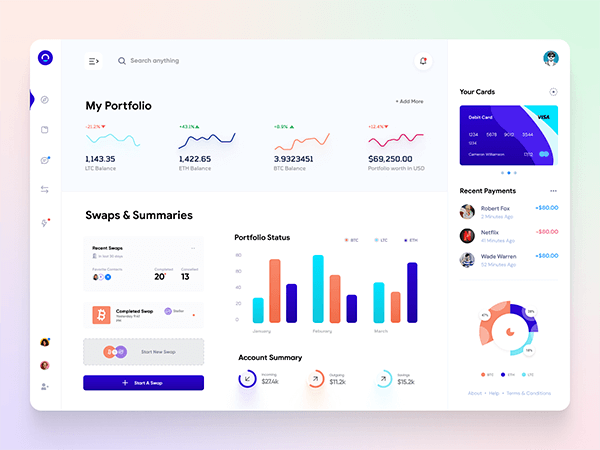

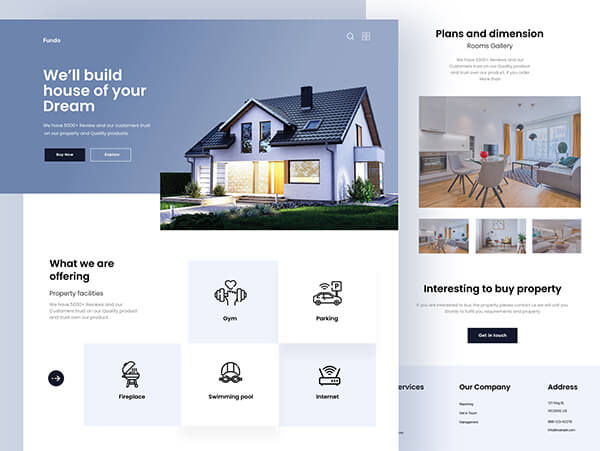

Beside, Im an experienced web developer specializing in managing blog sites for approximately 5 years. Additionally, I have a proven track record of building e-commerce websites for various companies, delivering successful projects tailored to their needs. With a strong background in both design and coding, I possess a wealth of knowledge in the field. Throughout my career, I have worked on various promotional websites and educational web applications, achieving significant milestones and garnering client satisfaction. I strive to provide solutions that meet the needs of my clients, leveraging my innovative ideas and technical expertise.

What i'm doing

-

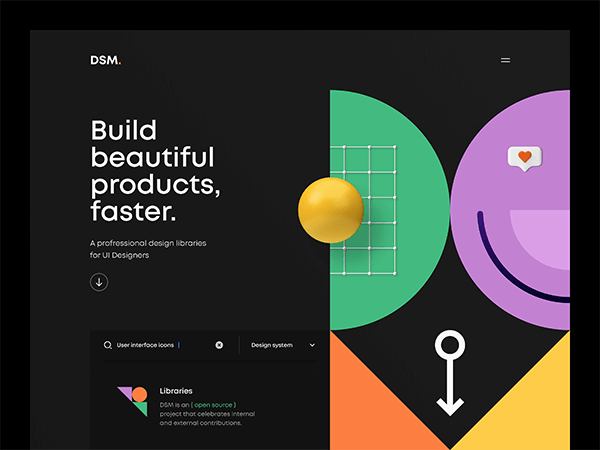

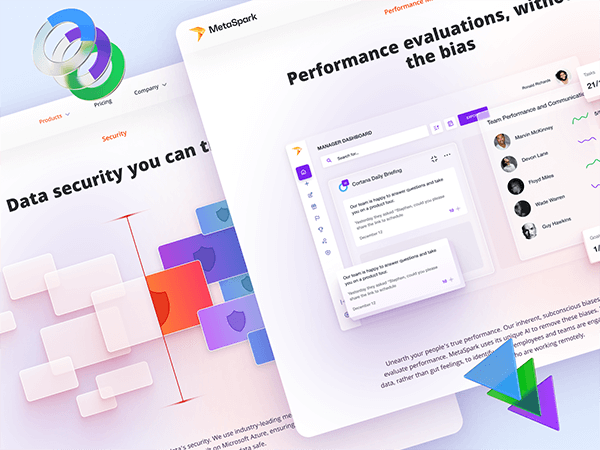

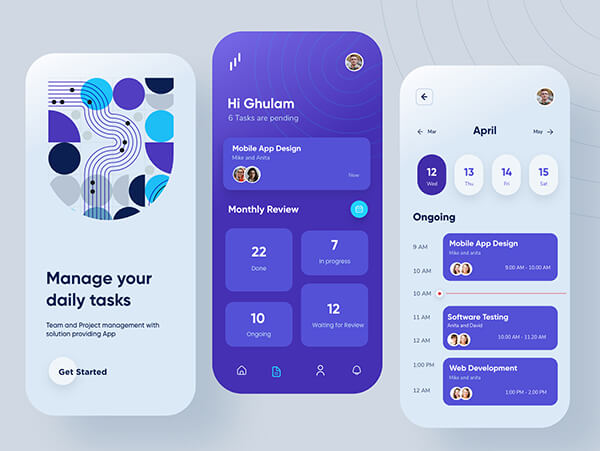

Web design

The most modern and high-quality design made at a professional level.

-

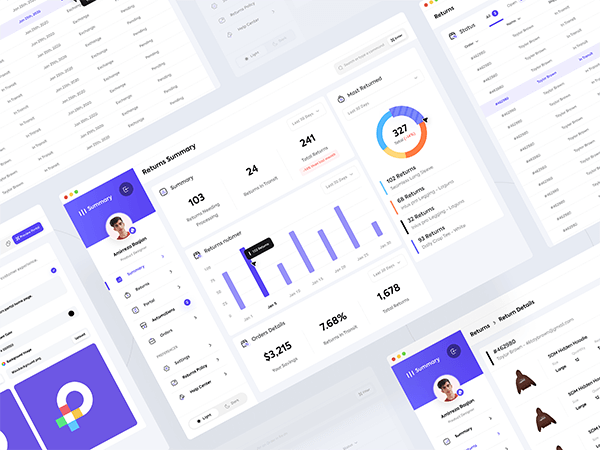

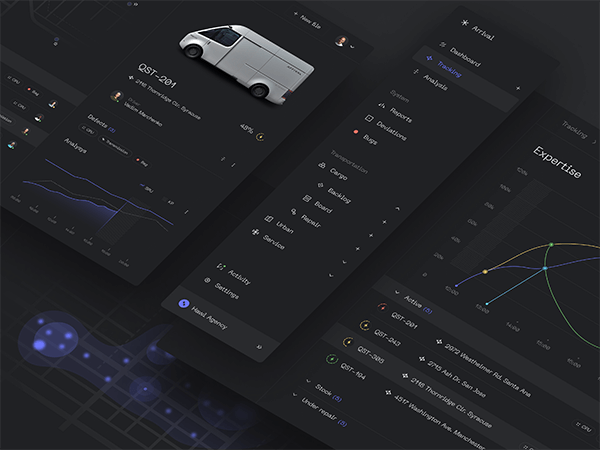

Web development

High-quality development of sites at the professional level.

-

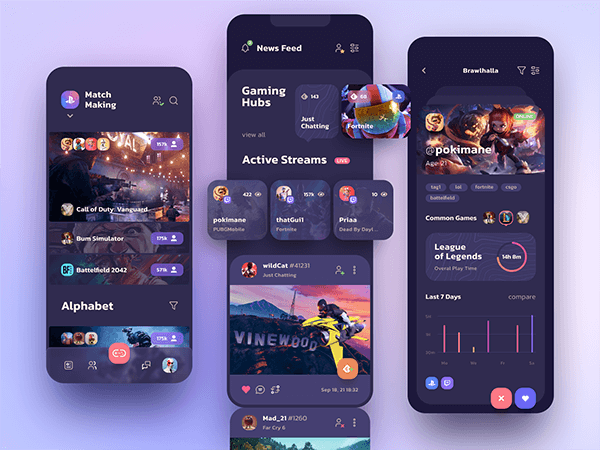

Mobile apps

Professional development of applications for iOS and Android.

-

Photography

I make high-quality photos of any category at a professional level.

Testimonials